Tyranny

Grainger uses the word “tyranny” (or one of its variants) nine times in The Sugar-Cane. Over the course of the poem, the term appears to shift subtly from a personification of the “insidious tyrant death” (I.328) who stalks British colonists and destroys European plants in the torrid climate of the tropics, to a more traditional application of the term against Britain’s military and colonial foes. In Book IV, however, “tyranny” begins to multiply in the text, referring variously to the black legend of Spanish colonialism to the more generic tyranny of slavery, the tyranny of insects and parasites that afflict human beings, and the tyranny of enslavers who need colonial laws to restrain their violent impulses. Given this wide range of uses, it is worth asking what, exactly, tyranny means to Grainger. And why is his use of it in the The Sugar-Cane important?

To the ancient Greeks, a tyrant (τύραννος) was either a person who had usurped power from the legitimate ruler or an absolute ruler who could not be restrained by legal or social convention. During the Age of Revolutions—the period spanning from approximately 1775 to 1848—the word tyranny became a common rallying cry for people across the Atlantic world seeking to establish independent systems of self-governance. Students of U.S. history will be familiar with Thomas Jefferson’s list of grievances against Britain in the Declaration of Independence. Introducing those grievances, Jefferson writes, “The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.” In the 1790s, French soldiers marching to battle sang, “Contre nous de la tyrannie / L’étendard sanglant est levé!” (Against us, Tyranny’s / Bloody flag is raised), lines that would soon be enshrined in the French national anthem. And on 1 January 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared independence for the Republic of Haiti, writing, “And you, people who have too long been unfortunate, witness the oath that we are talking, remember that I have counted on your fidelity and courage when I entered the pursuit of liberty to fight the despotism and the tyranny against which you had struggled for fourteen years; remember that I have sacrificed everything to fly to your defense, parents, children, fortune, and now I am rich only in your liberty; that my name has become a horror to all those who want slavery, and that despots and tyrants never utter it unless to curse the day that I was born.”1

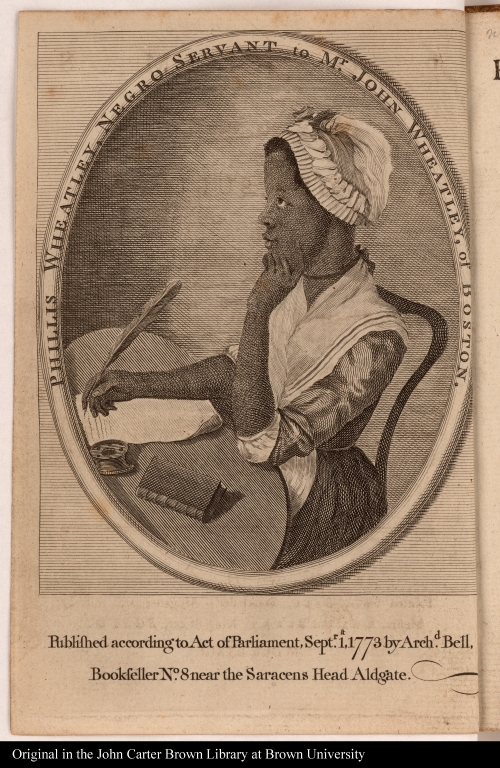

The historical and literary link between tyranny and slavery is long and vexed. When Dessalines invokes the specter of slavery in the Haitian Declaration of Independence, he means it literally: having only recently expelled Napoleon’s army from St. Domingue, the Haitians were determined to prevent slavery from ever returning to their country. Nevertheless, despite the force of Dessalines’ literal association, the Americans and French who fought in their own revolutions relied on a metaphorical link between tyranny and slavery in which they portrayed themselves as resisting figural enslavement at the hands of foreign tyrants. Eighteenth-century writers certainly understood the irony of revolutionaries professing their horror at the thought of losing their liberty and being enslaved while being enslavers themselves. Perhaps the keenest observer of this irony is Phillis Wheatley, the enslaved African poet who would use it to great effect in the poem titled “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” published in her 1773 Poems on Various Subjects. Here, Wheatley highlights the metaphorical link between tyranny and slavery that men like Thomas Jefferson and Tom Paine would make later in the decade only to juxtapose it to the actual tyranny of her own enslavement:

No more, America, in mournful strain [15]

of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shalt thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’enslave the land.

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song, [20]

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat: [25]

What pangs excruciating must molest, What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast? Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray [30]

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?2

Wheatley’s poem is an ironic reminder not to take claims like Jefferson’s literally. Reading about the kidnapping and enslavement that she suffered during her life pushes readers to reconsider the literary affect implicit in any metaphorical representation of slavery by propertied men in the eighteenth century. In turn, this irony likewise asks us to consider the full and complicated valence of the word “tyranny” in The Sugar-Cane. Grainger certainly knew that it was impossible to invoke tyranny in the context of Caribbean plantations without also immediately invoking slavery. And yet he takes time to get there. His goal of promoting the production of sugar and of defending the use of enslaved labor in the sugar trade produces a formal and thematic tension that erupts at various moments in the poem.

We encourage readers to read for “tyranny” and to consider how Grainger’s use of the term changes over the length of The Sugar-Cane. Does he use it consistently from beginning to end? Who are the tyrants and who are the victims of tyranny at various points in the poem? How does Grainger use the term strategically in Book IV, where he must confront the relation between tyranny and slavery to the British Empire? How do the varying uses of tyranny undermine or sustain Grainger’s ideological goals in the poem?

Note: For more on tyranny in The Sugar-Cane, see Steven W. Thomas’s “Doctoring Ideology: James Grainger’s The Sugar Cane and the Bodies of Empire.”

—Cristobal Silva

“Phillis Wheatley,” engraved plate from Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, London, 1773, frontispiece.

“Phillis Wheatley,” engraved plate from Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, London, 1773, frontispiece.

- While yet the Sun, in cloudless lustre, shines: [320]

- And draw their humid train o’er half the isle.

- Unhappy he! who journeys then from home,

- No shade to screen him. His untimely fate

- His wife, his babes, his friends, will soon deplore;

- Unless hot wines, dry cloaths, and friction’s aid, [325]

- His fleeting spirits stay. Yet not even these,

- Nor all Apollo’s arts,3 will always bribe

- The insidious tyrant death, thrice tyrant here:

- Else good Amyntor,4 him the graces lov’d,

- Wisdom caress’d, and Themis5 call’d her own, [330]

- Had liv’d by all admir’d, had now perus’d

-

“These lines, with all the malice of a friend.”6

- YET future rains the careful may foretell:

- Mosquitos, sand-flies, seek the shelter’d roof…

VER. 334. Mosquitos,] This is a Spanish word, signifying a Gnat, or Fly. The are very troublesome, especially to strangers, whom they bite unmercifully, causing a yellow coloured tumour, attended with excessive itching. Ugly ulcers have often been occasioned by scratching those swellings, in persons of a bad habit of body. Though natives of the West-Indies, they are not less common in the coldest regions; for Mr. Maupertuis7 takes notice how troublesome they were to him and his attendants on the snowy summit of certain mountains within the arctic circle. They, however, chiefly love shady, moist, and warm places. Accordingly they are commonest to be met with in the corners of rooms, towards evening, and before rain. They are so light, as not to be felt when they pitch on the skin; and, as soon as they have darted in their proboscis, fly off, so that the first intimation one has of being bit by them, is the itching tumour. Warm lime-juice is its remedy. The Mosquito makes a humming noise, especially in the night-time.

- Pauses the wind.—Anon the savage East

- Bids his wing’d tempests more relentless rave; [355]

- Now brighter, vaster corruscations8 flash;

- Deepens the deluge; nearer thunders roll;

- Earth trembles; ocean reels; and, in her fangs,

- Grim Desolation tears the shrieking isle,

- Ere rosy Morn possess the ethereal plain, [360]

-

To pour on darkness the full flood of day.—

- NOR does the hurricane’s all-wasting wrath

- Alone bring ruin on its founding wing:

- Even calms are dreadful, and the fiery South

- Oft reigns a tyrant in these fervid isles: [365]

- For, from its burning furnace, when it breathes,

- Europe and Asia’s vegetable sons,

- Touch’d by its tainting vapour, shrivel’d, die.9

- The hardiest children of the rocks repine:

- And all the upland Tropic-plants hang down [370]

- Their drooping heads; shew arid, coil’d, adust.——

- The main itself seems parted into streams,

- Clear as a mirror; and, with deadly scents,

- Annoys the rower; who, heart-fainting, eyes

- The sails hang idly, noiseless, from the mast….10 [375]

- From tyrants wrung, the many or the few.

- By wealth, by titles, by ambition’s lure,

- Not to be tempted from fair honour’s path:

- While others, falsely flattering their Prince, [295]

- Bold disapprov’d, or by oblique surmise

- Their terror hinted, of the people arm’d;

- Indignant, in the senate, he uprose,

- And, with the well-urg’d energy of zeal,

- Their specious, subtle sophistry disprov’d; [300]

- The importance, the necessity display’d,

- Of civil armies, freedom’s surest guard!

- Nor in the senate didst thou11 only win

- The palm of eloquence,12 securely bold;

- But rear’d’st thy banners, fluttering in the wind: [305]

- Kent,13 from each hamlet, pour’d her marshal’d swains,

-

To hurl defiance on the threatening Gaul.14

- THY foaming coppers15 well with fewel feed;

- For a clear, strong, continued fire improves

- Thy muscovado’s16 colour, and its grain.— [310]

- Yet vehement heat, protracted, will consume

- Thy vessels, whether from the martial mine…

VER. 312. Thy vessels,] The vessels, wherein the Cane-juice is reduced to Sugar by coction, are either made of iron or of copper. Each sort hath its advantages and

- The earth’s dark surface; where sulphureous flames, [170]

- Oft from their vapoury prisons bursting wild,

- To dire explosion give the cavern’d deep,

- And in dread ruin all its inmates whelm?—

- Nor fateful only is the bursting flame;

- The exhalations of the deep-dug mine, [175]

- Tho’ slow, shake from their wings as sure a death.

- With what intense severity of pain

- Hath the afflicted muse, in Scotia,17 seen

- The miners rack’d, who toil for fatal lead?18

- What cramps, what palsies19 shake their feeble limbs, [180]

- Who, on the margin of the rocky Drave,20

-

Trace silver’s fluent ore?21 Yet white men these!

- HOW far more happy ye, than those poor slaves,

- Who, whilom, under native, gracious chiefs,

- Incas22 and emperors, long time enjoy’d [185]

- Mild government, with every sweet of life,

- In blissful climates? See them dragg’d in chains,

- By proud insulting tyrants,23 to the mines

- Which once they call’d their own, and then despis’d!…

VER. 181. rocky Drave,] A river in Hungary, on whose banks are found mines of quicksilver.

- ‘Twould be the fond ambition of her soul,

- To quell tyrannic sway;24 knock off the chains [235]

- Of heart-debasing slavery; give to man,

- Of every colour and of every clime,

- Freedom, which stamps him image of his God.

- Then laws, Oppression’s scourge, fair Virtue’s prop,

- Offspring of Wisdom! should impartial reign, [240]

- To knit the whole in well-accorded strife:

- Servants, not slaves;25 of choice, and not compell’d;

-

The Blacks should cultivate the Cane-land isles.

- SAY, shall the muse the various ills recount,26

- Which Negroe-nations feel? Shall she describe [245]

- The worm that subtly winds into their flesh,27

- All as they bathe them in their native streams?

- There, with fell increment, it soon attains

- A direful length of harm. Yet, if due skill,

- And proper circumspection are employed, [250]

- It may be won its volumes to wind round

- A leaden cylinder: But, O, beware,

- No rashness practise; else ‘twill surely snap,

- And suddenly, retreating, dire produce

- An annual lameness to the tortured Moor….28 [255]

- YET, of the ills which torture Libya’s29 sons, [290]

- Worms tyrannize the worst. They, Proteus-like,30

- Each symptom of each malady assume;

- And, under every mask, the assassins kill.

- Now in the guise of horrid spasms, they writhe

- The tortured body, and all sense o’er-power. [295]

- Sometimes, like Mania,31 with her head downcast,

- They cause the wretch in solitude to pine;

- Or frantic, bursting from the strongest chains,

- To frown with look terrific, not his own.

- Sometimes like Ague,32 with a shivering mien, [300]

- The teeth gnash fearful, and the blood runs chill:

- Anon the ferment maddens in the veins,

- And a false vigour animates the frame.

- Again, the dropsy’s33 bloated mask they steal;

-

Or, “melt with minings of the hectic fire.”34 [305]

- SAY, to such various mimic forms of death;

- What remedies shall puzzled art oppose?—

- Thanks to the Almighty, in each path-way hedge,

- Rank cow-itch35 grows, whose sharp unnumber’d stings,

- Sheath’d in Melasses,36 from their dens expell, [310]

- Fell dens of death, the reptile lurking foe….

VER. 309. Cow-itch] See notes in Book II.

- Felt his heart wither on his farthest throne.

- Perennial source of population thou!

- While scanty peasants plough the flowery plains

- Of purple Enna;37 from the Belgian fens,38 [330]

- What swarms of useful citizens spring up,

- Hatch’d by thy fostering wing. Ah where is flown

- That dauntless free-born spirit, which of old,

- Taught them to shake off the tyrannic yoke

- Of Spains insulting King;39 on whose wide realms, [335]

- The sun still shone with undiminished beam?

- Parent of wealth! in vain, coy nature hoards

- Her gold and diamonds; toil, thy firm compeer,

- And industry of unremitting nerve,

- Scale the cleft mountain, the loud torrent brave, [340]

- Plunge to the center, and thro’ Nature’s wiles,

- (Led on by skill of penetrative soul)

- Her following close, her secret treasures find,

- To pour them plenteous on the laughing world.

- On thee Sylvanus,40 thee each rural god, [345]

- On thee chief Ceres,41 with unfailing love

- And fond distinction, emulously gaze.

- In vain hath nature pour’d vast seas between

- Far-distant kingdoms; endless storms in vain…

- To every Negroe, as the candle-weed42

- Expands his blossoms to the cloudy sky,

- And moist Aquarius43 melts in daily showers; [615]

- A wooly vestment give, (this Wiltshire weaves)44

- Warm to repel chill Night’s unwholesome dews:

- While strong coarse linen, from the Scotian loom,

-

Wards off the fervours of the burning day.

- THE truly great, tho’ from a hostile clime, [620]

- The sacred Nine45 embalm; then, Muses, chant,

- In grateful numbers, Gallic Lewis’46 praise:

- For private murder quell’d; for laurel’d47 arts,

- Invented, cherish’d in his native realm;

- For rapine48 punish’d; for grim famine fed; [625]

- For sly chicane49 expell’d the wrangling bar;

- And rightful Themis50 seated on her throne:

- But, chief, for those mild laws his wisdom fram’d,

- DID such, in these green isles which Albion53 claims, [630]

- Did such obtain; the muse, at midnight-hour…

VER. 613. candle-weed] This shrub, which produces a yellow flower somewhat resembling a narcissus,54 makes a beautiful hedge, and blows about November. It grows wild every where. It is said to be diuretic,55 but this I do not know from experience.

-

See Declaration of Independence at the National Archives; The Marseillaise; and Julia Gaffield, ed. The Haitian Declaration of Independence: Creation, Context, and Legacy. ↩︎

-

See Phillis Wheatley, “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for North America, &c.” Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London, 1773. 73-75. ↩︎

-

The Greek god Apollo was associated with healing and disease. ↩︎

-

King of Thessalian Hellas and the father of Phoenix, one of Achilles’s Myrmidons. ↩︎

-

In Greek mythology, Themis was the Titan daughter of Uranus and Gaia. She was the goddess of wisdom and good counsel; she also was the personification of justice and the interpreter of the gods’ will. ↩︎

-

Gilmore identifies this quotation as an adaptation from Edward Young’s The Universal Passion. Satire III. To the Right Honourable Mr. Dodington (1). ↩︎

-

Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698-1759), French mathematician, biologist, and astronomer who led an expedition to northern Finland to measure the length of a degree along the meridian. ↩︎

-

Vibratory or quivering flashes of light; lightning. ↩︎

-

Grainger refers to the unsuitability of some Old World plants to the tropical Caribbean climate. Europeans nevertheless transplanted as many familiar Old World plants as they could to the Caribbean and, in doing so, transformed its ecology. They transplanted animals and diseases as well. This transplantation process is now known as the Columbian Exchange and included the movement of plants, animals, and diseases in both directions across the Atlantic. ↩︎

-

Refers to the doldrums, also called intertropical convergence zones, where prevailing (or trade) winds disappear and ships become immobile for days on end. ↩︎

-

According to Gilmore, refers to Robert Marsham, 2nd Baron Romney (1712-1793), who married Priscilla Pym, the heiress of the St. Kitts planter Charles Pym. ↩︎

-

Prize for speech. In the ancient Greek Olympics, winners were awarded palm fronds. ↩︎

-

Kent faces France. ↩︎

-

France. ↩︎

-

Copper pots used for boiling cane juice. ↩︎

-

A dark brown, unrefined sugar that was typically the end product of the sugar-making process in the Caribbean. Often described as unrefined since it was usually processed further in Europe and lightened in color before being sold to consumers. ↩︎

-

Scotia is the Latin name for Scotland. ↩︎

-

Southwestern Scotland had produced lead since the Roman period. The Scottish Habeas Corpus Act of 1701 did not apply to those in servitude in the coal and lead mines of Scotland. As a result, they could be tied in serf-like bondage to employers by ancient custom. According to the terms of such bondage, they could be sold or leased with the undertaking of mining work and were counted as a part of employers’ inventory. Also, vagabonds and their families could be seized and returned to work. Born in Scotland himself, Grainger was aware of this history, and this stanza deliberately compares enslaved Africans to Scottish miners to mitigate the violence of the African slave trade. It would not be until 1774 that an emancipation act forbade mine owners from accepting new servitudes and provided for the emancipation of existing workers who had served for a certain number of years. Only in 1799 were all miners legally freed. ↩︎

-

Paralysis of the skeletal muscles. ↩︎

-

A river in central Europe that forms the boundary between Croatia and Hungary. ↩︎

-

Quicksilver or mercury, which was a major export of the region. Among the effects of continued exposure to mercury are palsies (line 180) and loss of teeth (line 193). ↩︎

-

The Incan Empire extended from modern Ecuador to Chile in the early sixteenth century, when Spanish conquistadors arrived and imposed colonial rule. In the fifteen lines that follow, Grainger relies on the trope of the Black Legend to suggest that the suffering of the Incas at the hands of the Spanish was far worse than anything experienced by enslaved persons working on British sugar plantations. In particular, the silver mines at Potosí in Upper Peru (modern Bolivia) drove Spanish settlement, and indigenous populations were subjected to the encomienda system, in which an encomendero accepted tribute and obligatory labor from natives in return for protection. In the early seventeenth century, this system gave way to a corregimiento system that established networks of provincial governors who managed the labor distribution and tributary arrangements. Enslaved Africans were also imported and put to work in mines when labor ran short and gradually surpassed the natives in population. Besides silver, gold deposits were found throughout the Andes from Venezuela to Chile, and European colonists greatly expanded the extant mining work of the indigenous Americans in scale. ↩︎

-

The Spanish conquistadors. ↩︎

-

A direct acknowledgment of the tyranny of slavery. Note that tyranny, an increasingly discussed topic during the late eighteenth-century Age of Revolutions, appears several more times in Book IV. ↩︎

-

Grainger claims that even after they were freed, formerly enslaved Africans would continue to work on sugar plantations by choice, but this sentiment was a pro-slavery fantasy that was not borne out by reality after emancipation. ↩︎

-

The abrupt shift in tone marks Grainger’s turn away from his abolitionist fantasy and toward a policy of amelioration, in which physicians like himself were to play a central role. Recall his words at the end of the preface: “I beg leave to be understood as a physician, and not as a poet.” See also Steven Thomas’ “Doctoring Ideology.” ↩︎

-

Guinea worm or the dragon worm (Dracunculus medinensis) is a parasitic nematode acquired by drinking water contaminated by the water flea (genus Cyclops), which carries the worm’s larvae. The larvae break through the stomach lining and enter the bloodstream, growing to full size within a year. A pregnant female worm lives in connective tissues beneath the skin and eventually will release its larvae into a large blister, usually on the legs or arms. The worm’s migration produces such symptoms as itching, giddiness, breathing difficulties, vomiting, and diarrhea. The worm may come out spontaneously with the released larvae, but treatment typically involves attaching the worm to the end of a stick and winding it slowly out of the opening in the skin over the course of several days (the “leaden cylinder” that Grainger mentions in line 252 refers to this form of treatment). A broken worm causes an extreme allergic reaction that can be fatal, and blisters on the skin may ulcerate and become infected, resulting in an abscess and the “annual lameness” of which Grainger warns in line 255. Today, the worm may also be treated through anthelmintics. ↩︎

-

Moor, a name for a native or inhabitant of Mauretania in North Africa (modern Morocco and Algeria versus Mauritania). ↩︎

-

Not the modern nation of Libya but the Libyan desert in the eastern Sahara. Grainger uses “Lybia” and “Lybians” several times in Book IV of The Sugar-Cane to signify Africa and Africans. ↩︎

-

In Greek mythology, Proteus, an old man and shepherd on the island of Pharos near Egypt, was able to shape-shift. The worms’ ability to cause multiple maladies and symptoms is equated to Proteus’s shape-shifting abilities. ↩︎

-

Roman and Etruscan goddess of the dead who ruled the underworld with Mantus. ↩︎

-

An acute or high fever or a disease that causes such. Often used to refer to malaria. ↩︎

-

An accumulation of fluid in the soft tissue of the body, more commonly known as dropsy. The modern term is edema (or oedema). ↩︎

-

Gilmore identifies this line as an adaption from John Armstrong’s description of a lung infection in The Art of Preserving Health (1744). ↩︎

-

Cowitch (Mucuna pruriens), a viny plant that produces severe itching after contact with skin. Was used on sugar plantations as compost, forage, and cattle feed. Its seeds destroy intestinal parasites. Likely native to tropical Asia and possibly Africa. ↩︎

-

Molasses, the thick, brown, uncrystallized syrup drained from raw sugar. ↩︎

-

City and province in central Sicily and location of a Sicilian slave revolt (134-132 BCE). ↩︎

-

Refers to the High Fens, a highland plateau in the eastern Belgian province of Liege. ↩︎

-

The region Grainger refers to as the Belgian fens had been part of the Netherlands, which were under Spanish control from the sixteenth century until the War of Spanish Succession. After the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), the Spanish ceded the Netherlands to Charles VI of Austria. ↩︎

-

Commonly spelled Silvanus, the Roman god of the countryside often associated with woodlands and agriculture. ↩︎

-

The Italo-Roman goddess of growth and agriculture. ↩︎

-

Senna alata, also known today as the candle bush or king of the forest. Its native range is southwestern Mexico to the tropical Americas. ↩︎

-

Aquarius is often represented by a figure pouring water from a jar. ↩︎

-

Wiltshire, a county in England, has been a center of the English weaving and woolen industry for nearly 4000 years. ↩︎

-

The nine muses of art, literature, and science. ↩︎

-

Gallic Lewis refers to Louis XIV (1638-1715), king of France from 1643-1715. ↩︎

-

Laurel (bay leaf) crown, often associated with poetic achievement. ↩︎

-

The act or practice of seizing and taking away by force the property of others. ↩︎

-

A subterfuge, petty trick, or quibble. ↩︎

-

Greek goddess of law and justice. ↩︎

-

Ethiop and Ethiopia were sometimes used by the Greeks and Romans to refer to a specific people and region of Africa, but Ethiop was used to designate a generically black African as well. Ethiopians also were referenced in a classical proverb about “washing the Ethiopian” or turning black skin white. The proverb and subsequent versions, which were widely circulated in the early modern period and eighteenth century, framed the task as impossible and hence were used in justifications of racial difference based on skin color. ↩︎

-

Grainger is referring to the Code noir, a royal edict issued by Louis XIV in 1685. The Code noir contained sixty articles regulating the treatment of the enslaved in the French Caribbean. Although Grainger praises it as protecting the enslaved from abuse, other eighteenth-century observers condemned it as proving the inhumanity of the institution of slavery, since it still allowed enslavers to inflict harsh punishments on the enslaved and treat them as property. ↩︎

-

Albion, a name of ancient Celtic origin for Britain or England. The term may also derive from the Latin word for white (albus) and refer to the white cliffs of Dover. ↩︎

-

The genus Narcissus contains several species of plants with yellow flowers, including the daffodil. ↩︎

-

A substance that promotes the excretion of urine. ↩︎