Munājāts attributed to ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib

Textuality

Munājāts attributed to ʿAlī circulated independently of his sermons, sayings, and letters collected in Nahj al-balāgha. Individual supplications have nonetheless enjoyed sustained exegetical attention.1 In terms of their textuality, whether Biḥār al-anwār includes any munājāt attributed to ʿAlī still needs fact-checking, but the modern Iranian scholar Muḥammad Bāqir Maḥmūdī who compiled Nahj al-saʻādah fī mustadrak nahj al-balāghah did not cite Biḥār al-anwār as a source for his fourth volume on selected supplications attributed to ʿAlī.

In this volume, four munājāts of varying lengths and interspersed between other prayers attributed to ʿAlī are not treated as a unity. The only verse munājāt among the four, anthologized in the most widely used contemporary Shīʿīte prayer manuals Mafātīḥ al-jinān, is not introduced with a chain of transmission and it is unclear when this verse munājāt was first canonized. The current collection includes five related texts: a 15th century takhmīs based on it, a 16th century copy commissioned for the private use of the Ottoman şeyhülislâm Hoca Sadettin Efendi (d.1599), an 18th century copy and a 19th century copy with interlinear translations for Persian speakers, and an undated album of calligraphy that takes its individual bayts for artistic representation.

The other three prose munājāts are much longer and, when juxtaposed, reveal so much textual overlap as to suggest that they may be three versions of a single prayer. Maḥmūdī’s edition offers two useful pieces of textual information: one munājāt narrated on the authority of the eleventh Shīʿīte Imām al-Ḥasan al-‘Askarī2 is based on an old manuscript found in the library of Imam Riẓa in Khorasan;3 another that bears a distinct chain of transmission comes from Dustūr ma‘ālim al-ḥikam, a collection of sayings and maxims attributed to ʻAlī compiled by the 11th century Fatimid jurist al-Quḍā‘ī. The former, known as al-munājāt al-ilāhīyāt in Iran, has a complete manuscript featured in the current collection. The latter has a new critical edition prepared and translated into English by Tahera Qutbuddin. Qutbuddin edited the munājāt collected in Dustūr with considerations of the Iraqi manuscript. She remarks on the textual overlap between these in a footnote: “The Iraqi manuscript contains roughly half of Dustūr 8.1, viz. 8.1.1–8.1.3, 8.1.16–8.1.18, 8.1.20–8.1.39, 8.1.67, 8.1.74, and part of 8.1.77. Moreover, it includes 9 short prayers that are not present in the Dustūr.”4 It’s worth noting that textual overlap appears in chunks rather than contiguously. Meanwhile, when thinking about the structural unity of munājāt texts – whether individual sentences were read as independent units or parts of a whole – we should bear in mind that these numbers reflect the editorial hand, not section divisions originally found in the manuscripts of Dustūr.5 For detailed comparisons between the three versions, see this document in the project repository.

The prose manuscript in this collection

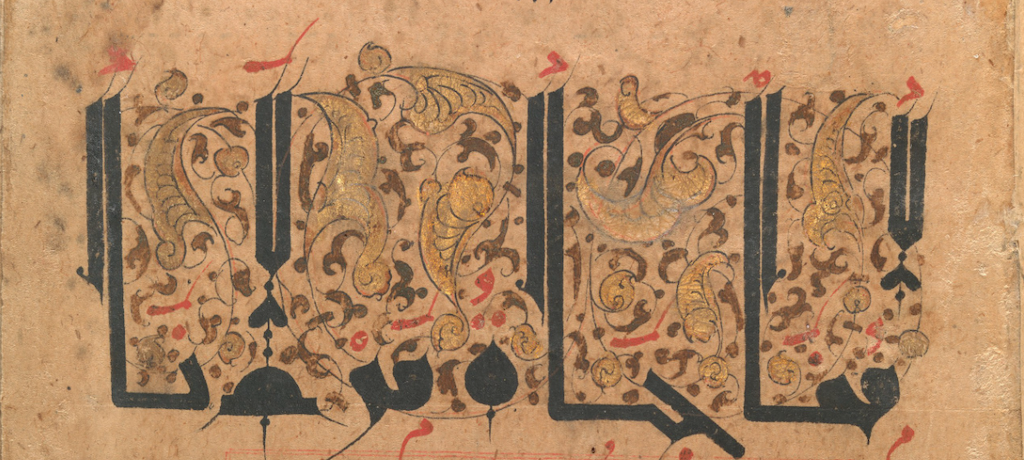

This manuscript has two major pieces of calligraphy.

On the title page المُناجاةُ مَوْلانا (the munājāt of our lord)

On the following page بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم (bismala)

Both phrases are vocalized and annotated with miniature letters in subscript. Also written in red ink below the calligraphic title is the munājāt’s attribution to ʿAlī, repeated again towards the end of the ʾisnād. The only date in the text is the year in which the eleventh Imām passed away. The fourteen pages are numbered, and have complete catchwords. Except in rare cases,6 the gilded floral patterns can serve as puncuation marks in addition to their decorative function. The note beneath the phrase that ends the prayer, تَمَّتْ المُناجاتُ (the munājāt ended), was by a different hand and has been crossed out. Apart from the unreadable notes on the margin of page three, there are three instances of variant readings marked out by the letter خ (nuskhah) in a neatly red-lined box on pages eight, nine, and twelve. The marginal note on page fourteen is blurred because of water damage. A roundel or seal impression without recognizable inscription is in the lower left corner on page thirteen.

The prayer is copied as a continuum, without section divisions. The repeated invocation ilāhī, highlighted in red ink, indicates semantic pauses in the prayer. The abjectness of the speaker is striking:7

إلهي عَظُمَ جُرْمي إذْ كُنْتَ الْمُبارَزُ بِهِ وَكَبُرَ ذَنْبي، إذْ كُنْتَ المُطالَبُ بِهِ، إلا أنِّي إذا ذَكَرْتُ كَبِيرَ جُرْمي، وعَظِيمَ غُفْرانِكَ، وَجَدْتُ الحاصِلَ لي مِن بَينِهِما عَفْوَ رِضْوانِكَ

My God, how great was my crime, since you were the one it was directed against;

how grave was my sin, since you were the one it was directed against.

However, when I remembered the greatness of my fault and the enormity of your forgiveness,

between the two I found forgiveness by your grace to be my outcome.

As prominent is the use of rhetorical questions and parallelism, even as the speaker says الهي أَفْحَمَتْني ذُنوبي، وَقُطِعَتْ مَقالَتَي (My God, my sins struck me numb, my words were cut short). Parallelism is often instituted by adverbials of concession such as إنْ and إذ (if, even if, though) to the effect of dogged insistence. When combined with emphatic structures, parallelism reveals the irresistible eloquence of the speaker:8

إلهي قَلْبٌ حَشَوْتُهُ مِنْ مَحَبَّتِكَ في دارِ الدُّنيا، كَيف تَطَّلِعُ عَلَيْهِ نارٌ مُحْرِقَةٌ في لَظى؟

إلهي نَفْسٌ أَعْزَزْتَها بِتَأييدِ إيمانِكَ، كَيْفَ تُذِلُّها بَيْنَ أَطْباقِ نِيرَانِكَ؟

إلهي لِسانٌ كَسَوْتَهُ مِنْ تَماجيدِكَ أنِيقَ أَثْوابِها، كَيْفَ تَهْوِي إِلَيْهِ مِنْ النَّارِ مُشْعلاتُ الْتِهابِها؟

My God, the heart I filled with love for you in the abode of this world, how can scorching fire in hell come upon it?

My God, the soul you cherished through strengthening belief in you, how can you humiliate it between layers of your flames?

My God, the tongue you dressed in your elegantly garbed glorifications, how do you blow toward it the igniting fire?

This pithy self-dissection into heart, soul, and tongue, attempts to affirm the reciprocity of prayer: they belong to the speaker, but are curated by God. And perhaps most appropriate to the context of verbalizing needs, the speech act of praying itself is seen as impossible without divine sanction and pleasure: وَلَوْ لَمْ تُطْلِقْ لِسانِي بِدُعائِكَ ما دَعَوْتُ (if you had not loosened my tongue for invoking you, I would not have prayed).

Notes

-

For example, a three-volume commentary on du‘ā Kumayl by al-Shaykh Fāḍil al-Ṣaffā, Mawāhib al-layl fī sharḥ Duʻāʼ Kumayl, was published in 2019 and a Persian commentary on one of the munājāts attributed to ‘Ali by Firishtah Balūchī, Sharḥī bar munājāt-i Ḥazrat-i Amīr dar Masjid-i Kūfah, was published in 2015. ↩

-

See pg.27 at https://dlib.nyu.edu/aco/book/columbia_aco002247/33. ↩

-

See pg.37 at https://dlib.nyu.edu/aco/book/columbia_aco002247/43. ↩

-

The text and English translation of this munājāt can be found in the “Prayers and Supplications” chapter of A Treasury of Virtues: sayings, sermons and teachings of ʻAlī, with the One Hundred Proverbs Attributed to Al-Jāḥiẓ, Library of Arabic Literature, 2013, pp. 176-195; the footnote on textual comparison with the Iraqi manuscript is on page xxxvii. ↩

-

A 17th century Yemani manuscript of Dustūr is accessible at https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4350012. The munājāt begins on 232b and ends on 241a. ↩

-

For example, the floral patterns at end of the sixth line from the top on page four and in the fourth line from the top on page five should move ahead a few words if meant to punctuate the sentence. ↩

-

on page 4. ↩

-

on pages 7-8. ↩